Why are vesicles coated?

Vesicles are a family of membrane-enclosed structures used for intracellular and extracellular transport of cargoes (both fat-soluble membrane proteins and water-soluble luminal proteins), providing routes for efficient protein exchange between membrane-enclosed compartments that do not require proteins to travel across membranes. Vesicular transport typically involves coat complexes (COPII, COPI, and clathrin), which regulate transport and confer directionality and specificity regarding the cargoes being trafficked. Vesicles bud from the donor compartment’s membrane to move towards and fuse with the receiving compartment or the extracellular milieu, expelling their contents into it. Though together termed ‘transport vesicles’, they have diverse structures and functions, determined by their distinct coat compositions that specify the compartments from and to which they travel. Coat proteins are highly conserved structures involved in vesicular transport across all eukaryotic cells (Harrison & Kirchhausen, 2010), highlighting their importance in the effective communication within the endomembrane system. By controlling every step of vesicular transport, from the initial membrane deformation to the packaging of cargoes, vesicle coats allow membrane-enclosed structures to perform specialised functions by maintaining their unique biochemical environments.

The three general types of coated vesicles—COPII-coated vesicles, COPI-coated vesicles, and clathrin-coated vesicles (CCVs)—contribute to the various vesicular transport pathways (Figure 1): the secretory pathway transports cargo from the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) to the Golgi apparatus and eventually to the plasma membrane (PM) or lysosomes; the endocytic pathway traffic proteins from the PM into the cell; the retrieval pathway returns membrane and proteins to their originating compartments. (Alberts et al., 2015)

Figure 1. Vesicular transport pathways. Red, green, and blue arrows indicate secretory, endocytic, and retrieval pathways, respectively. Red and blue coats are COPII and COPI coat complexes, respectively. Green/orange coats are clathrin coat complexes. Only explained processes are shown. Created with BioRender.com.

General mechanisms underlying all vesicular transport involving coat complexes

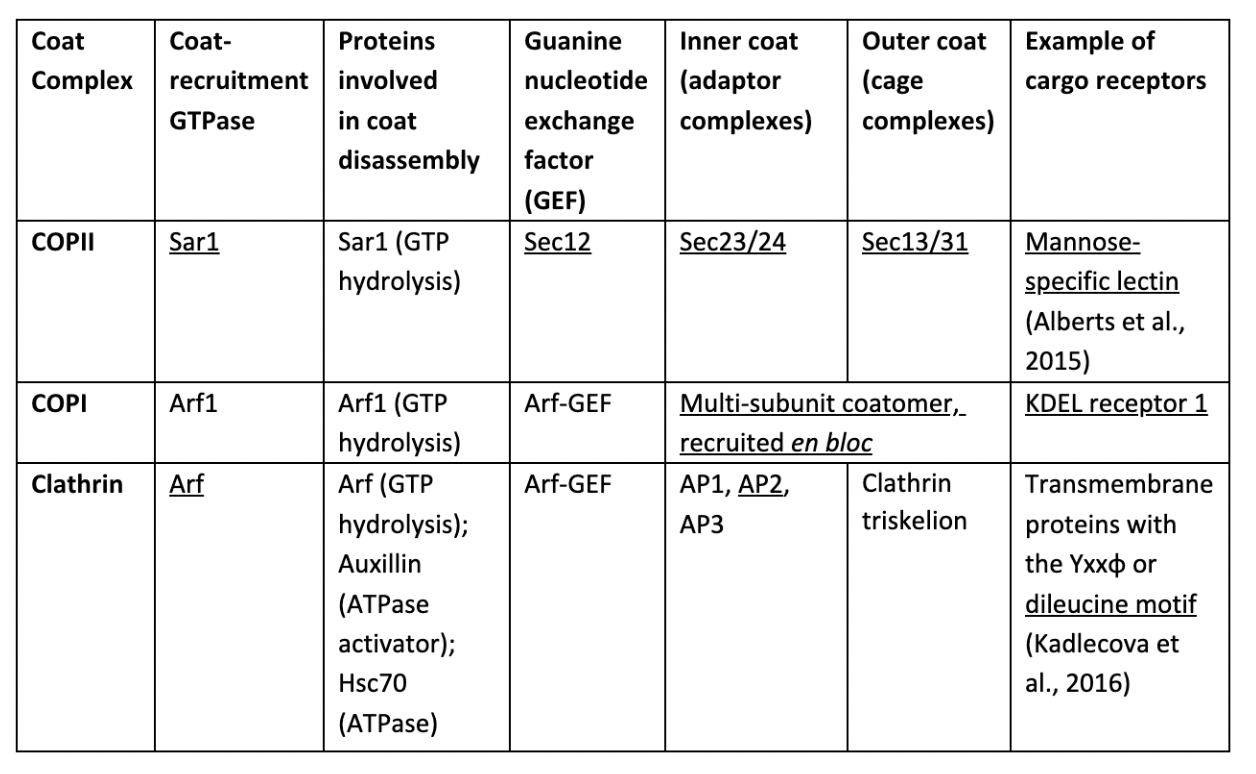

Vesicular transport proceeds sequentially, with common principle steps and components (Table 1). Coat-recruitment GEFs (guanine nucleotide exchange factors) convert membrane-bound monomeric GTPases from their GDP-bound state to a GTP-bound state, providing high-affinity binding sites for coat complexes. Assembly of coat complexes (composed of adaptor complexes and cage complexes) around membranes induces membrane curvature, increasing the likelihood of coat subunits binding to adjacent areas, demonstrating cooperativity. Adaptor proteins act as physical bridges between cage complexes and membranes. They selectively bind to transmembrane proteins, some of which act as cargo receptors that bind to specific luminal cargoes, packaging them into vesicles. Cage complexes polymerise into a polyhedral lattice, shaping the vesicle. The interactions between coat subunits are flexible to allow vesicles to vary in shapes and sizes to accommodate diverse types of cargo, while subunits themselves are rigid enough to impact membrane curvature. Once coated, the cargo-filled vesicle pinches off the membrane and moves towards its target compartment. Transport is directed by coats recognising specific Rab proteins attached to cytosolic membrane surfaces of different compartments, such as Rab1 unique to ER membranes. Finally, GTPase hydrolyses GTP, which triggers coat disassembly, allowing vesicles to fuse with their target membranes. The mechanisms stimulating GTP hydrolysis remain unknown, but coat components may act as GTPase-activating proteins (GAPs). (Alberts et al., 2015)

Table 1. Coat complexes, their constituents, and proteins essential for their functions. Underlined proteins will be discussed in detail. (Faini et al., 2013)

Vesicle fusion is thermodynamically unfavourable. SNARE proteins help overcome this energy barrier. V-SNAREs on vesicular membranes form SNAREpin complexes with complementary t-SNAREs on target membranes, releasing approximately 2.67∙10-9 J per SNAREpin formed. This is coupled to membrane fusion, making the overall process entropic and therefore spontaneous. (Mostafavi et al., 2017)

Different coat complexes, their structures and functions

Figure 2. Molecular composition and structure of different vesicular coat complexes. Only subunits that are explained are labelled. Created with BioRender.com.

A) COPII

COPII-coated vesicles traffic cargoes to be secreted from ER to Golgi. Together, Sar1, Sec23/24, and Sec13/31 form the COPII coat (Figure 2). Vesicle formation is initiated when Sec12 activates Sar1, which binds to an ER exit site (differentiated subdomain of ER adjacent to vesicular-tubular clusters, where membrane lacks bound ribosomes (García-Mata et al., 2003) (Figure 1)), triggering the assembly of Sec23/24. Sec23/24 binds to Sar1-GTP, forming the heterotrimeric inner coat subunit. Sec24 both acts as Sar1-GAP and binds to cargo receptors. Sec13/31 heterodimers are then assembled, forming a cuboctahedral cage. (Faini et al., 2013)

Entry of proteins into vesicles can be a selective or default process. Sec23/24 adaptor complexes recognise and bind to membrane cargoes displaying exit signals, including cargo receptors that concentrate luminal cargoes into vesicles. For example, the mannose-specific lectins: ERGIC-53, transmembrane proteins acting as cargo receptors, bind mannoses attached to blood coagulation factors V and VIII (Nyfeler et al., 2006). This ensures the efficient secretion of these factors, preventing excessive bleeding upon injury. After budding, the COPII coats shed, allowing vesicles to fuse with each other and form vesicular-tubular clusters. These then move along microtubule tracks to fuse with the Golgi. Proteins without exit signals, including ER-resident proteins, can escape the ER via COPII-coated vesicles. Though ER-resident proteins exit (passively) significantly slower than cargoes do (actively), this can lead to functional impairment of the ER over time without recycling mechanisms. (Alberts et al., 2015)

B) COPI

COPI-coated vesicles (Figure 2) contribute to retrograde trafficking, returning selected proteins from Golgi back to their donor compartment: the ER. The components that constitute the inner and outer COPI coat are recruited as preassembled heptameric complexes (coatomers), unlike COPII and clathrin coats (Faini et al., 2013). The reason behind this mechanism is currently unknown. Budding of COPI-coated vesicles from vesicular-tubular clusters is initiated almost immediately after fusion and continues after the clusters have fused with the Golgi (Alberts et al., 2015). This balances the flow of membrane between Golgi and ER, returns the escaped ER-resident proteins, and recycles cargo receptors and SNAREs that participated in the secretory pathway, preventing the depletion of materials that cells would otherwise need to constantly replenish.

The retrieval of cargoes via COPI-coated vesicles requires retrieval signals, of which there are two best-characterised types: KDEL sequence (ER retention signal), which binds to KDEL receptors, and KKXX (for ER membrane protein), which interact with COPI coat directly (Alberts et al., 2015). One such example is the binding immunoglobulin proteins (BiP)—ER chaperones—which dissociate from ER membrane proteins when misfolded proteins accumulate in the ER to bind misfolded proteins and support their refolding (Jin et al., 2017). However, their disassociation increases their chance of entering COPII-coated vesicles. Therefore, BiP possesses the KDEL sequence (Lys-Asp-Glu-Leu), which binds to KDEL receptor 1 on COPI complexes (Jin et al., 2017). Mimura et al. (2007) explored the role of KDEL sequence in BiP trafficking using transgenic mice that produced BiP lacking KDEL. Neonate mutants suffered from respiratory failure resulting from defective lamellar bodies in alveolar cells and lowered production of functional surfactant proteins. This underscores the importance of the retrieval pathway in maintaining ER’s function (maturation of proteins) and the dependence of this pathway on interactions between retrieval sequences and the COPI coat.

Furthermore, impaired COPI complexes are associated with amyloid plaque formation (a hallmark of Alzheimer’s) in mutant mice brains (Bettayeb et al., 2016). Precursors of amyloid are secreted rather than retrieved without functional COPI, leading to their accumulation, forming plaques. Thus, COPI complexes recycle escaped ER proteins and prevent the over-secretion of potentially harmful proteins.

C) Clathrin

From Golgi, proteins get trafficked via CCVs to either lysosomes for degradation or PM for exocytosis. CCVs are involved in numerous trafficking pathways. Their different adaptor proteins between the membrane and clathrin triskelia (Figure 2) specify their pathways—trans-Golgi to endosomes: AP1, trans-Golgi to PM and PM to endosomes: AP2, and trans-Golgi to lysosomes: AP3—and select cargoes to traffic (Alberts et al., 2015). Arf protein initiates the assembly of adaptor complexes, which then recruit the clathrin triskelia. A well-studied example of CCV uses the adaptor protein AP2 and is central to clathrin-mediated endocytosis (CME) (Kelly et al., 2014). In vitro studies suggested that phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2), a phosphorylated glycerophospholipid, triggers a conformational change of AP2 from a cargo-inaccessible state to an active state (Höning et al., 2005; Beacham et al., 2019), exposing its binding sites for both clathrin triskelia and membrane cargoes and cargo receptors containing either the Yxxφ (φ represents hydrophobic residue) or dileucine motif (Kadlecova et al., 2016). Therefore, AP2 proteins are only recruited to membranes high in PIP2, allowing phosphatidylinositol kinase to control the rate of CCV formation and therefore of CME. Additionally, binding to clathrin triskelia strengthens the interaction between AP2 and the membrane (Alberts et al., 2015), exemplifying bidirectional stabilisation. Dynamin (GTPase) couples GTP hydrolysis to detachment of vesicles from their donor membranes. Clathrin coat disassembly is unique as it also requires ATP hydrolysis by Hsc70, in addition to GTP hydrolysis by Arf. CCVs are extensively regulated by various factors, ensuring that their formation and fusion only occur at the appropriate locations and times.

However, CME is exploited by viruses like HIV-1 to enter and infect cells. HIV-1 coat contains the dileucine motif, allowing them to be endocytosed by the cell. The reduction of AP2 effectively lowers the rate of HIV-1 entry, revealing the role of AP2 in recognising the motif on the virus coat. Despite being extensively regulated and central to protein intake, CME facilitates viral infections. (Byland et al., 2007)

Conclusion

Coat complexes cooperate with each other and coordinate with other molecules to regulate vesicle formation and fusion temporally and spatially. By selecting and packaging cargoes and directing transport, they allow effective material exchange between different membrane-enclose compartments, thereby preserving the unique biochemical identities of such compartments needed to perform their specialized functions. When direct observation of their mechanisms is difficult, analyzing the consequences of removing coat components (COPI in mutant mice) or interrupting their functions (removing KDEL from BiP) can allow investigation of their roles. Further research into the mechanisms underlying vesicular transport in humans (or at least in vivo, following ethical guidelines) can help better address neurological conditions like Alzheimer’s and viral infections like that caused by HIV-1.

Reference List:

Alberts, B. et al. (2015) Molecular biology of the cell, New York, NY: Garland Science, pp. 695-739.

Beacham, G.M., Partlow, E.A. & Hollopeter, G. (2019) Conformational regulation of AP1 and AP2 clathrin adaptor complexes. Traffic, 20(10), 741–751. https://doi.org/10.1111/tra.12677

Bettayeb, K. et al. (2016) Relevance of the COPI complex for Alzheimer's disease progression in vivo. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 113(19), 5418–5423. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1604176113.

Byland, R. et al. (2007) A conserved Dileucine motif mediates clathrin and AP-2–dependent endocytosis of the HIV-1 envelope protein. Molecular Biology of the Cell, 18(2), 414–425. https://doi.org/10.1091/mbc.e06-06-0535.

Faini, M. et al. (2013) Vesicle coats: Structure, function, and general principles of Assembly. Trends in Cell Biology, 23(6), 279–288. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2013.01.005.

García-Mata, R. et al. (2003) ADP-ribosylation factor/COPI-dependent events at the endoplasmic reticulum-golgi interface are regulated by the Guanine Nucleotide Exchange factor GBF1. Molecular Biology of the Cell, 14(6), 2250–2261. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-11-0730.

Harrison, S.C. & Kirchhausen, T., 2010. Conservation in vesicle coats. Nature, 466(7310), 1048–1049. doi: 10.1038/4661048a.

Höning, S. et al. (2005) Phosphatidylinositol-(4,5)-bisphosphate regulates sorting signal recognition by the clathrin-associated adaptor complex AP2. Molecular Cell, 18(5), 519–531. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.04.019.

Jin, H., Komita, M. & Aoe, T. (2017) The role of BIP retrieval by the KDEL receptor in the early secretory pathway and its effect on protein quality control and neurodegeneration. Frontiers in Molecular Neuroscience, 10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnmol.2017.00222.

Kadlecova, Z. et al. (2016) Regulation of clathrin-mediated endocytosis by hierarchical allosteric activation of AP2. Journal of Cell Biology, 216(1), 167–179. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201608071.

Kelly, B.T. et al. (2014) AP2 controls clathrin polymerization with a membrane-activated switch. Science, 345(6195), 459–463. doi: 10.1126/science.1254836.

Mimura, N. et al. (2007) Aberrant quality control in the endoplasmic reticulum impairs the biosynthesis of pulmonary surfactant in mice expressing mutant BIP. Cell Death & Differentiation, 14(8), 1475–1485. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402151.

Mostafavi, H. et al., 2017. Entropic forces drive self-organization and membrane fusion by SNARE proteins. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 114(21), 5455–5460. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1611506114.

Nyfeler, B. et al. (2006) Cargo selectivity of the ERGIC-53/MCFD2 transport receptor complex. Traffic, 7(11), 1473–1481. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2006.00483.x.